I’m enjoying a local bar the way I like it- nearly empty, quiet but for the band in the next room that I’ll shortly go in to support, and just me and the bartender discussing books. They have to bus tables, I need to write and wait for my food order. It’s a genial end to the conversation.

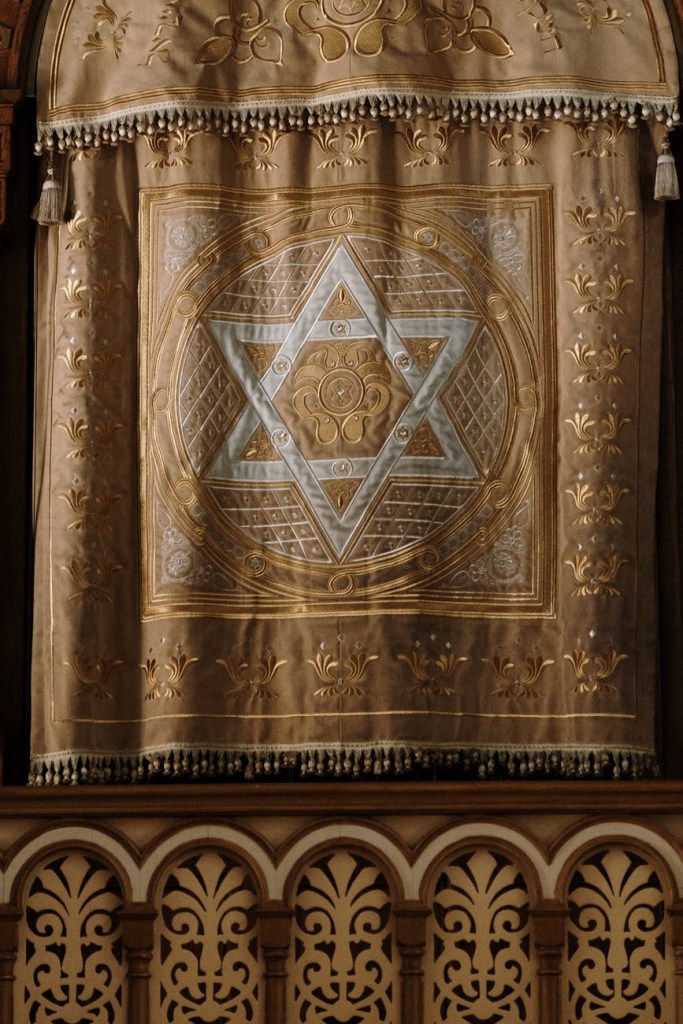

Leikam Brewing is Jewish woman-owned brewery in Southeast Portland that embodies what I want to be myself- unapologetically and openly itself and also a hub of its community. It’s a Jewish space that’s not just for Jews. If you’re part of the community, you don’t need to be part of the Tribe.

I’ve knocked back two beers over the course of my conversation with the bartender about the virtues and flaws of various fantasy series. One was a French Toast-inspired ale called “Ain’t No Challah-Back Girl” and the other a stout called “Mob Barley.” If it’s not Jewish puns, it’s music- or both- and I’m not mad about it. Going here tonight felt needed, and not just because I knew a particularly good skewer truck was going to be selling their wares and I have an unhealthy need for their black sesame flatbread with roasted garlic toum spread.

The first month of 2026 in the US was not fantastic. An activist mother of three, Renee Good, was murdered- shot three times at point blank range- by an agent of the state who proceeded to brag about it, and the government unabashedly bullshit the public about how the woman was a “domestic terrorist” and “tried to run/ran the agent over” when their own camera shows otherwise. They did it again to a VA nurse- Alex Pretti- whose last words were “Are you okay?” to a woman these same agents had just pepper-sprayed and pushed to the pavement.

While still processing this, I got treated to reports of leftists- the guys meant to oppose this kind of fascist, Big Brother crap- lined up outside at New York synagogue chanting about how much they love Hamas. Later, I’d see tweets asking if the VA nurse was a Zionist, and I’ve grown too used to them showing up to every protest or event with their flags and keffiyehs yelling “collective liberation!” as they attempt to hijack someone else’s efforts to organize.

After over two years of feeling chased out of leftist spaces by these ignorant shmucks who are- at best- useful idiots parroting slogans, I think I’m well within my moral rights to wish a plague on both their houses, wait for both parties to beat the tar out of each other, and rebuild better once they’ve burned each other out.

It can never be that simple though. The fact that it goes against every bone in my body to look at people suffering and say “not my problem” is only part of it. It’s that I once again get to watch my identity be made convenient.

Continue reading →